(as usual, click on pictures and text to make them legible)

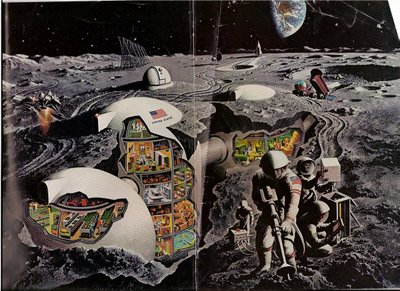

(as usual, click on pictures and text to make them legible)"How would you like to play ping-pong on the moon?" is the question I always ask myself when I look at this illustration I cut out from an old National Geographic a few years ago. I can't remember the date of publication for this picture, drawn by science fiction artist Davis Metzler, but I'm pretty sure it ran sometime between Neil Armstrong's 1969 landing and Apollo 17 in 1972, which was the last time any human has set foot on the moon.

Though people during the early Apollo missions might have assumed moon homes were the logical next step, it would take a pretty giant leap of the imagination to picture something like this happening anytime in our lifetimes, especially since no one has been there in 34 years. So what happened to dampen our enthusiasm for colonizing the moon, besides a couple of space shuttle crashes?

In her 2003 book, "Rocket Dreams: How the Space Age Shaped Our Vision of a World Beyond," journalist Marina Benjamin takes a philosophical approach to why the moon landings didn't lead to permanent bases like this one.

"Homesickness prevailed over the imperative to press outward and upward," Benjamin writes. "Images of our lush fragile globe beamed back from afar made cooling, protective converts of the most forward-thinking rationalists, and before long many of these had swaddled themselves in environmentalism. Exploration was out and conservation was in ... Within less than a decade of landing on the Moon, all our outward-bound aspirations had more or less turned in on themselves."

Or to quote Elton John lyricist Bernie Taupin from their song Rocket Man, "it's lonely out in space."

Like a kid who goes too far out of his head on drugs and gets homesick for an innocent, normative state, the astronauts in the Apollo missions expressed a longing to return to earth even before they left. The lunar missions also mirror psychedelic experiences in that people who try psychedelic drugs usually only do so for a couple of year time period before they decide it's time to move on. Maybe the people involved in the space program felt they had done as much lunar exploration as they needed to. I have no doubt that humans will make contact with the moon again someday, but it might be by a later civilization, or at least a different nation state than the ones in power now.

In the arts, however, the moon remains as inspring as ever. What's not to be inspired by? It's bright, round, changes shape each day and takes on different qualities each month which are known to many native peoples by many different names. The moon exerts a commanding influence on the waves we surf and the women we love. It's also the subject of a lot of poetry, both excellent and abysmal.

Fortunately, you don't have to be John Donne to write about the moon's influence effectively. In fact, it is often the most simple lunar observations that remain memorable. One evening in the Rheinland, when four of us decided to go on our own little space adventure in the hills of the Kottenforst, Wade decided he wasn't feeling well and broke away from the group to enjoy a more urban sojourn. While walking around the city listening to his discman, he paid special attention to the moon, which kept threatening to disappear for good behind wisps of passing clouds. "Come on, moon!" he kept shouting. "You're the only friend I have left!"

It was actually while visiting Wade in Madison, Wisconsin under the glare of the Tim Burton moon that I first postulated my theory of Lunar Poetic Inversion. The theory suggests that because earth-bound humans look to the moon to receive and inspire our most poetic thoughts, any words actually spoken on its surface (should we get the chance to visit) would logically be the most authentic, poetic sentiments we are capable of expressing, however trite or plain-faced they may sound on other surfaces (i.e. "earth is beautiful", "I miss my wife", "if only I had a taco"). I abandoned the theory of Lunar Poetic Inversion once I realized that it doesn't make any sense, but I still think it's a pretty thought.

To sum it up, no matter what scientific or artistic accomlishments it inspires, instilling those of us on earth with a sense of childlike wonder will always be the moon's true legacy. That, and a delectable, pre-packaged pastry known as the banana moon pie.

No comments:

Post a Comment